Michelle Emmons served as the education and outreach coordinator from 2014-2017 for the Middle Fork Willamette Watershed Council before moving on to start a new business model combining outdoor stewardship and adventure guiding in the Willamette Basin.

I never would have believed fishing could be as adrenaline pumping as skydiving , downhill mountain biking or kayaking class IV waters – but it is; and even better, there’s a long-term purpose associated with “hunting” lamprey – a goal for sustaining the species, as well as a key food source for both man and animal (including salmon). Preserving the tradition of lamprey fishing also provides a key thread in the social and cultural fabric of many Native Americans.

I met Kelly Dirksen, Tribal Fish and Wildlife Program Manager for the Confederated Tribes of Grande Ronde, while preparing a program for the Middle Fork Willamette Watershed Council’s Science Pub series. Kelly presented a fascinating story about the lamprey translocation process, and titillated our staff with a tentative invitation to join him for a lamprey harvest in the following months, dependent on migration timing and water levels. Of course, we couldn’t say no! The privilege, and the gratitude, was ours; as was the curiosity, excitement and honor to have been asked to participate alongside Tribal members.

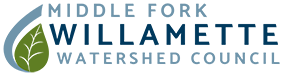

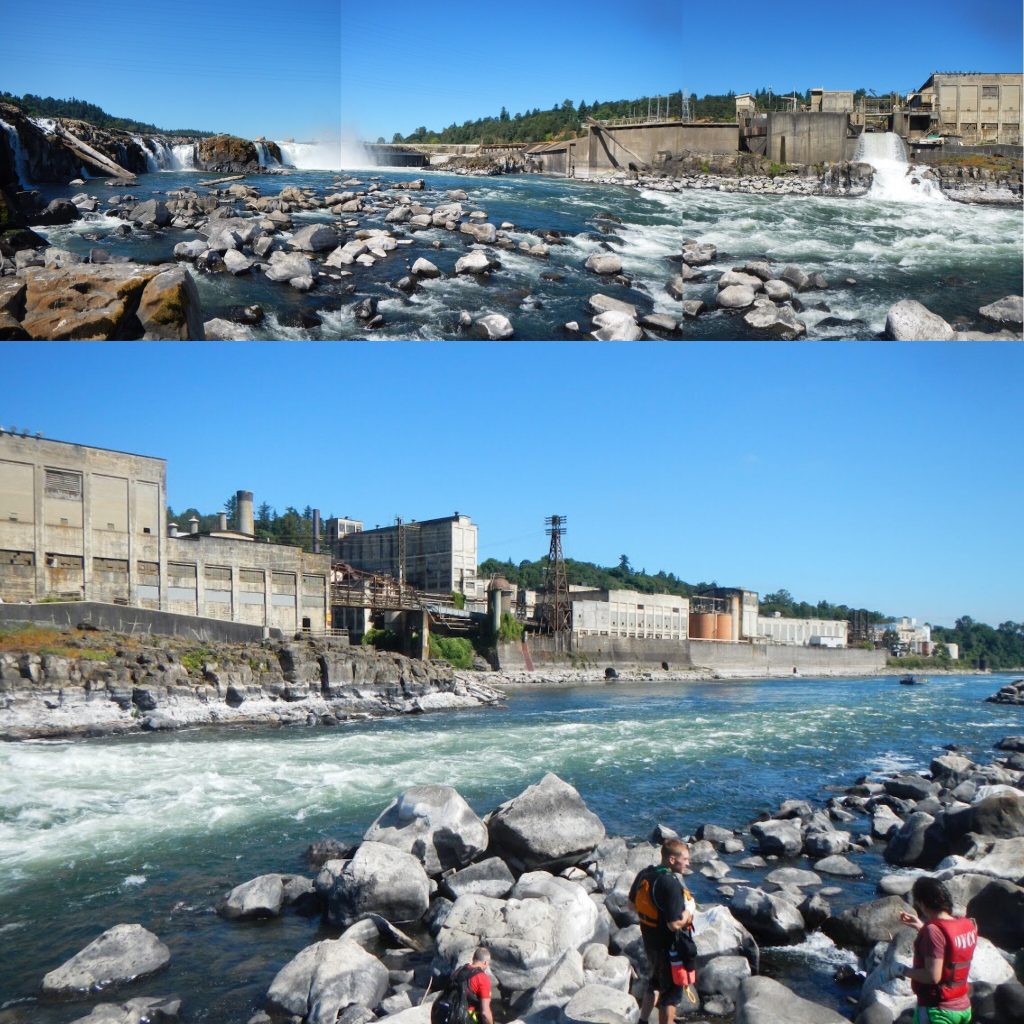

We met Kelly and his assistant biologist, Torey Wakeland, at Sportcraft Marina, a moorage and small motorboat retail center just downriver of Willamette Falls. We jumped aboard the Tribal Fish and Wildlife Dept. boat and motored out toward the base of the falls.

On the way out, Kelly explained why harvests were not as abundant as they used to be due to over-harvesting and dam management practices that make the fish particularly vulnerable when flashboard installation is used to regulate hydroelectric flows during seasonal low water levels. To help with these issues, the Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife has improved lamprey passage with specialized structures. Meanwhile, the Tribal Fisheries continue to work with regulating agencies to study lamprey migration and develop a plan to sustain and stabilize future populations of lamprey for food supply.

As we approached the base of the falls, Kelly warned us, “The rocks are slick; once wet, very slick. We are in low flow conditions so be aware of rebar and debris beneath the surface.” He then distributed some cloth gloves to us as we donned our life jackets and wading boots. We clambered off the boat and over several rocks to reach the first harvest area. It looked like a raging cauldron of boiling water, exacerbated by the overhead spillage, serving as an eggbeater. Kelly jumped right in, immersing his entire body beneath the falls and popping up, just beyond the spillway. Gloves in play, he shouted instructions above the din of the spray. “Find a hole, grab the fish, and hand off as many as you can get!”

With that, he dipped back under the surface and reached into hidden rock crevices. Less than a second later, he sprang up with both arms outstretched, gripping a massive, writhing tentacle in each hand, reaching for the mesh bag we’d brought along to temporarily store the fish after capturing them. Now there were fish jumping out of the hole, left and right, as he reached back into it again and again, filling the bag with just under a dozen specimens. “Wanna try?” he offered, with a wide grin.

I can’t possibly explain the exhilaration and satisfaction of fishing by hand… to be submerged beneath a waterfall, reaching into the unknown abyss of darkness and rocky tunnels; re-emerging in an explosion of half-sized boa constrictors, one in each hand – a giant “muscle” of an animal – twisting and squirming even harder as I double down to hold onto it; either passing it up to the next person in a chain to the storage bag or keeping it under control enough to place it in the bag myself. Meanwhile, many more of them continued surging through the rapids all around me, in a desperate attempt to escape our mission. It was unreal.

We moved on to various spots, at one point, ferrying ourselves through a small but strong current, pushing us toward a fallen log in the water. My mind raced for an instant, as I thought about my raft guide training around strainers, but I quickly set my anxiety on the back burner as I refreshed my swimming pace across the current, getting kicked while almost paddling over the top of another co-worker to get to “shore”.

After exploring about a half-dozen areas, Kelly slogged the heavy harvest over his shoulders, swimming and wading through a maze of rock outcroppings where we observed a somewhat scraggly blue heron up close, and a large salmon taking refuge in the shadows of rocks and woody debris in calm water. Once back in the boat, Kelly disposed the bag of lamprey into a large cooler, and we were back at the dock with an estimated 60 fish in less than two hours of effort.

Truly one of the most profound experiences of my life, I couldn’t believe it was over already. The act of “hunting for food” coupled with the challenge of overcoming my fears of physical danger, drove me back to my instinct, and the present moment. It provided me a window of insight into a different culture, generating a new level of respect, awe and reverence for preservation of a species, and a way of life. I am deeply grateful to Kelly, Torey, and the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde for the opportunity to participate in this tradition – truly a gift of inspiration and a memory not soon forgotten.

Click here for more information about the Grande Ronde Tribal Fisheries Fish and Wildlife Program.